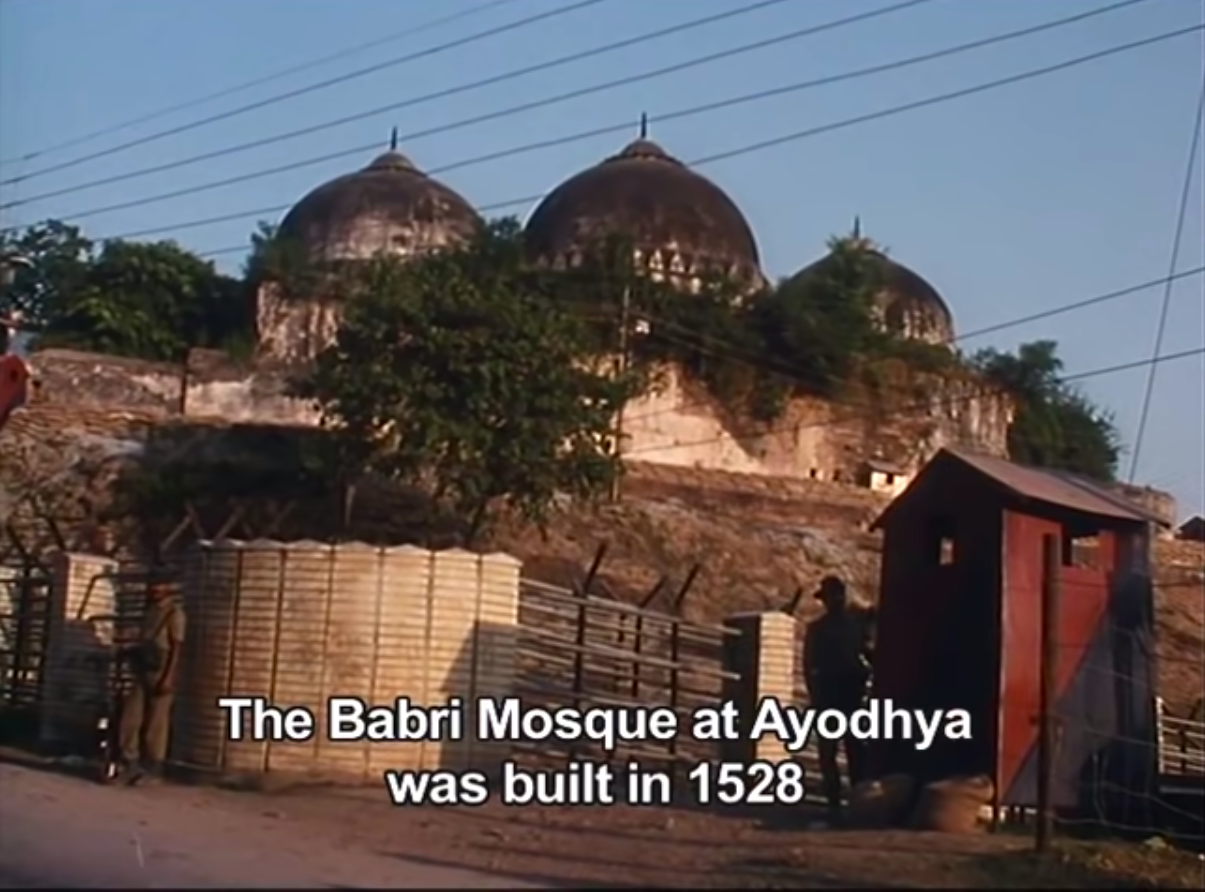

India has been a secular state ever since Independence (1947). But as religious fundamentalist influence grows over the masses of India, the nation's secular fabric gets threatened. One of the most crucial case in point is the demolition of the 16th century mosque in Ayodhya, known as the "Babri Masjid"—which is celebrated by the Hindu Nationalists of India.

Babri Masjid is believed to be constructed by Mughal Emperor, Babur. The Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) claims that the mosque was built at the birth-site of the Lord Ram on the orders of Babur—after razing a pre-existing Ram temple. They are determined to build a new Ram temple on the same site.

This controversial issue, which recently, in 2019, came to yet a controversial conclusion after several successive governments failed to resolve it—has led to many religious riots, costing thousands of lives, culminating in the mosque's destruction by militant Hindu 'Karsevaks', allegedly under VHP leadership, in December of 1992. The religious violence that followed, spread throughout India, leaving more than 5,000 dead, and causing thousands of Muslims to flee their homes.

In this essay, I look at what happened in Ayodhya through analyzing Anand Patwardhan's "Ram Ke Naam"—also known as—"In the Name of God"—a documentary that covers the campaign waged by the quasi-militant Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP)—to destroy Babri Masjid.

Filmed prior to the mosque's demolition, Ram Ke Naam examines the motivations which would ultimately lead to the drastic actions of Hindu nationalists, as well as the efforts of secular Indians—many of whom are Hindus as well—to combat the religious intolerance and hatred that has seized India in the name of God.

Ram Ke Naam is an investigative documentary which studies—through multiple interviews—the happenings at Ayodhya around the Babri Masjid, how this controversy surrounding it began. It attempts to understand the collective mindset of Hindu nationalists—why they wish that a Ram temple should be built at the site of the Babri masjid and what they feel about the communal riots that have been caused due to the controversy.

Concurrently, the documentary also attempts to understand the opinions of people who oppose the VHP’s Ram temple campaign. It contains anecdotes about how this campaign affected the poor, the lower castes, and the untouchables as well—thus making a clear contrast between the opinions and experiences of people from privileged upper castes (particularly those who support the campaign) and the the people from underprivileged groups viz. lower castes, untouchables, and Muslims. The film mainly highlights 4 aspects of this controversy—politicisation of religion, communalism, religious fundamentalism, and classism/casteism. I intend to analyse this film on these lines.

The Babri masjid was built in 1528, in Ayodhya. Circa 1580, Tulsidas wrote Ramcharitmanas, making the legend of Lord Ram available to a larger audience—while incorporating vernacular language. By the 19th century, the city of Ayodhya, due to it being the birthplace of Lord Ram—as stated in the Ramcharitamanas—was filled with Ram temples. Interestingly, a huge chunk of the Ram temples claimed itself to be the very site of Lord Ram’s birth. This period was contemporaries with the Indian Subcontinent under British colonial rule. The Britshers, as they implemented their “divide and rule” strategy, are often quoted spreading the rumour that the Babri masjid was the very site of Lord Ram’s birth, and that the mosque was built by Babur after razing an existing Ram temple that existed there.

This led to communal tensions among Indians, but it was short-lived, and through mutual compromise, people maintained communal harmony by agreeing to worship their gods side-by-side, in the same site itself. It was not until December 1949, when the next controversy surrounding the mosque arose. Some militant Hindu nationalists from the Akhil Bhartiya Ramayana Mahasabha, secretly placed idols of the Hindu deity inside the mosque, making it look like God Ram had made a divine appearance, to agitate Hindu possession of the site—leading to communal tensions. The state government ordered the removal of the idols, which the local police refused to do citing that it could lead to riots. KK Nayar, who was the district magistrate then, decided that until a decision from the courts comes, the mosque shall be locked and no one can access it. Yet, Hindu nationalists still demanded that a grand Ram temple should be built at the site of the Babri masjid (after razing the Masjid), regardless of whatever the courts decide.

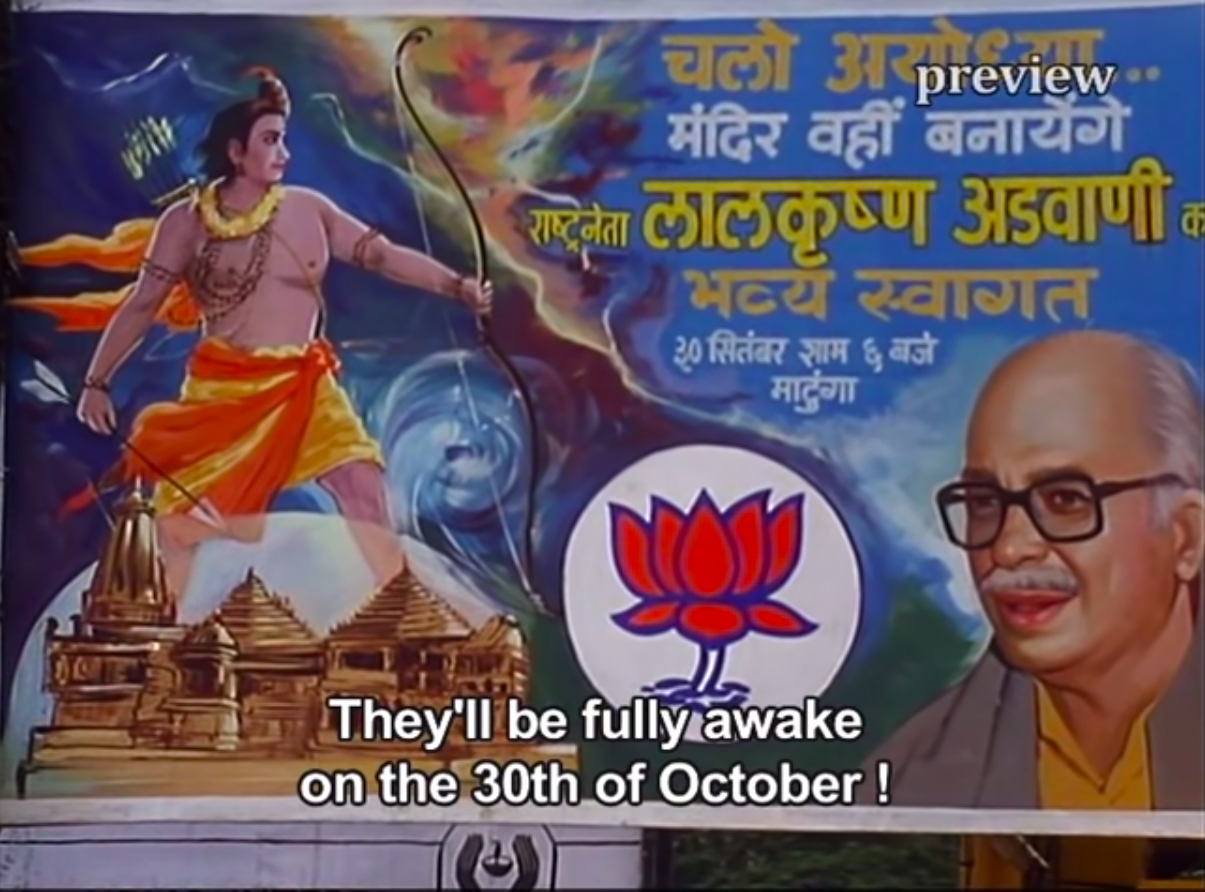

The film begins with a shot of a political campaign poster [of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)] featuring the Hindu warrior-king deity, Lord Ram, in large size, standing over/behind the imagined-by-all Ram Temple. The poster also features Lal Krishna Advani—the president of BJP. We hear Advani giving his speech in the background, “I appeal to you, Ram Jyoti (the divine light of Ram) will give you all the inspiration needed for the betterment of the life; all what is needed for the betterment of life is only Ram; if there is no Ram, there is no survival”. Advani, as a politician, or BJP, as a political party, appealing to the public with religious promises is a classic example of politicisation of religion. Politics—in purely electoral context—is a competition where parties race for the support of the people (which gives them access to power) by attending to their various demands and interests.

There are various subjects of interest, as far as people are concerned, over which politics can be played—like employment and food security. While these are valid subjects of interest, emanating from the masses themselves, it is also possible to create interests. Both valid and/or vested, by political parties. In the case of politicisation of religion, Hindu religion being given a political identity (instead of leaving it for what it is, i.e., religion of faith), to serve a political agenda of Hindu Rashtra—the raison d’etre of BJP—is a classic example of creation of vested, (but not valid), interests.

The film shows why the VHP’s campaign is backed by the BJP. In the film, while interviewing some youth from the Bajarangdal—yet, another militant Hindu nationalist organisation—a youth revealed that the VHP, Bajarangdal and the BJP are all family organisations of one organisation—the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), and that Bajarangdal was the youth-wing of the VHP. The RSS—founded in 1925—is a Hindu nationalist organisation, and is the ideological wing of the BJP. The RSS has many “family organisations” since the 1930s, and today, the Family of the RSS, also known as the “Sangh Pariwar” the VHP, the BJP, and the Bajarangdal are some of the most prominent members of the family.

While the BJP (1980) is the electoral/political wing of the RSS, the VHP (1964) serves as a church-like establishment to represent the Hindu religion. As far as BJP is concerned, it served as the Hindu nationalist alternative to the rather popular, secular party, the Congress party. BJP was created by the RSS as a way of recruiting people into the Hindu nationalist fold, after it was banned as an organisation during Indira Gandhi’s National Emergency. Through BJP, RSS as well was able to upgrade its activities. RSS did (does) so by choosing senior former pracharaks (full time workers in the RSS) who are highly trained by the RSS, and placing them at the highest positions of decision making in the BJP. LK Advani, the then president of the BJP, was himself a pracharak in the RSS, before joining BJP, and the former BJP Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee as well was a pracharak. While the BJP did political campaigns; VHP did its own religious campaigns where it used different forms of imagery to influence people.

Coming back to the film, one instance shows some men crowding around a television to watch the telecast of a film produced by the VHP that depicts the supposed divine appearance of God Ram inside the Babri Masjid, on the night of December 23rd, 1949. It does so—so dramatically—that it perhaps, hypnotises those watching it. Not only this instance, in 1987, the broadcast of the Ramayana television series (based on Tulsidas’s Ramcharitamanas) as well did contribute to VHP’s Hindu nationalist cause. It further popularized the deity, reinforcing that God Ram was born in Ayodhya, (the place where Babri Masjid is located), and presenting Ram with the Hindu nationalist interpretation—as a warrior-God. Around 300 versions of Ramayana exist, yet, the one broadcasted on TV presented a very conservative and a masculinist interpretation.

As recorded in the film, LK Advani’s Rath Yatra to Ayodhya, starts from Somnath, Gujarat. I understand this is because in around 1950 the Government of India—notwithstanding claims to secularism and pluralism—assisted the renovation of a Hindu temple at Somnath. This temple was said to have been destroyed by Muslims during their rule. In 1951, at the inauguration of the temple, President Rajendra Prasad stated in his speech that this was a historic day, for India had “washed away the stigma of one thousand years of slavery”, this statement of his has been widely interpreted to mean that India was now finally free from a period of a thousand years of slavery, period of Muslim and British rule combined. Thus, this official act, by the President of India himself, of equating mosque with Muslim rule, thus slavery of Hindus, made it symbolic enough to start the Rath Yatra from Somnath itself.

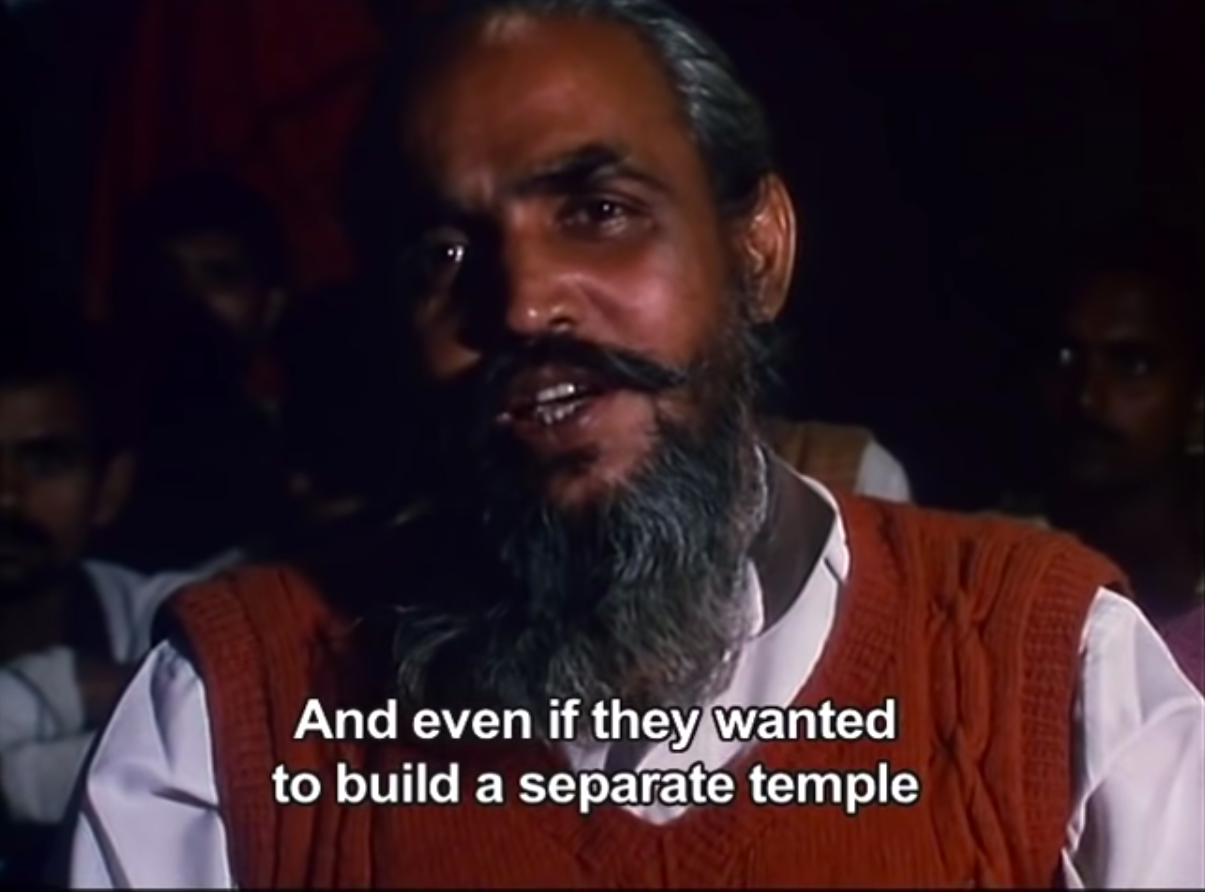

The court appointed priest for the Ram (Janmabhoomi) temple, Pujari Laldas seems to be the very voice of this documentary. His character seems to be the very message that this documentary is trying to construct and put across to its viewers. Laldas counters and criticizes the kind of religious fundamentalism that has swallowed the masses into itself, and dismisses the whole relevance of the controversy. He comments on the VHP’s real intentions in this controversy, and exposes it for not really genuinely believing in the cause they are so committed to. He says that this whole issue that the VHP has is making a "hype" out of is just a political “game” for achieving economic and political power, and this issue never really was about a temple. He reveals that the VHP has not once made a single offering or prayed at the Janmabhoomi shrine, yet the fight for a Ram temple. He says that there is no need for another temple, because in the Hindu (religion as a faith) culture, wherever there is a God present is considered a temple; even if there was a need for another temple, demolishing a place of worship to build another is unnecessary and wrong. He says that those who want to demolish the mosque just want to create communal tensions and collect Hindu votes—they don’t care if a genocide happens in the process. He explains that religious fundamentalists have very conveniently forgotten that there has always been unity among Hindus and Muslims, no trouble has been caused by anyone since 1949, people have been living in harmony, worshiping their respective gods side-by-side, and also that many temples with Ayodhya itself are built by Muslims, some of whom are a gesture of apology from their ancestors for the tyranny caused by their ancestors. He questions the purpose of the very proposed temple itself – at what cost should a temple be built? Why can’t the temple funds be used to aid the poor, like Mother Teressa does (did), is that not the legacy of God Ram, rather than the Hindu nationalist connotation he has been given? It’s a shame that such a bright ray of light in such darkness, saint-like Pujari Laldas, was murdered. While his murder was termed as a case of a simple land dispute, its rather obvious that it really was something else, that it was a case of revenge by Hindu fundamentalists, sanctioned by the state.

Another moving aspect of the film was the interview of the income tax officer, Vishwa Bandhu Gupta, who was victimised for doing his job too honestly and religiously. Vishwa Bandhu Gupta was investigating the VHP for tax scams, and he was suspended for sticking his neck down too deep. He was looking at where the VHP was getting its funding from even after being denied permission from the Reserve Bank of India to receive funds from foreign investors. He was stopped in the middle of his operation, transferred to Madras (Chennai), and the entire investigation was quashed in no time. He was even threatened with his life by 2 Hindu nationalists he refused to name. The disappointed and tearful look on his face as the camera zoomed into it was painful to see, it was as though the proverbial lump in his throat (the existence of which seemed rather obvious in the film, given the unstable emotional look on his face), was getting transferred into my own, as the viewer of this documentary.

At last, the class/caste aspects that this film covers in this controversy. In the entire film, we see that every Hindu nationalist the filmmakers come across/meet is a privileged upper caste Hindu, not one of them is a lower caste person or an untouchable. Whereas those on the side of the streets, on the farms, all of them happen to be poor and/or lower caste or untouchables. On interviewing them, many of them either have no clue as to what is going on, what this controversy is, or just don’t care about the controversy, because it in no way benefits them, and they feel it is only a waste of time because they have immediate responsibilities like feeding their families, and surviving. There was no show of any communal hatred. Yet, all of them expressed that they still faced caste-oppression. One Dalit woman, named Bhavandevi, who was interviewed in the film, said that her people aren’t even allowed anywhere near temples. With that said, why would she support the Ram temple cause? It shows that among these very Hindu nationalists who talk about Hindu unity, there exists a great deal of classism and casteism, and hypocrisy.

As the film comes to end, we see Pujari Laldas reciting a doha from Ramayana itself, “when the rains are heavy, and the grass grows so tall that its difficult to see the right path the same way when charlatans speak so much and so loudly that the truth gets hidden, you experience chaos, disorder, frenzy, madness. But these rains are short-lived, so, when the rains stop and the right path becomes visible and clear, you proceed in the right direction, the direction of reason”. This doha signifies that while the country is in turmoil today, we must not lose hope, for these heavy rains will soon end, and peace will be restored in the country again. The film then concludes with Bhavandevi saying that the temple is of no use to her and her people, when they aren’t even allowed anywhere near it in the first place – if an idol of a deity breaks, it may be replaced with another one; but when a living body gets torn apart during violence, with what will it replaced? Bhavandevi says that she is human, too, yet she is treated differently by people of her own race; her village is a birthplace to many of her kind, Untouchables, and they are being wrongly evicted—then there is a Ram whose birthplace everyone is after—why should she run after it, too?

Ram Ke Naam by the end of the film, asks the following important, yet difficult questions: why is it that people blind in their love for god forget what their god really preaches and become so vulnerable to leaders who preach hate and mislead, all in the name of God? Why is it that people confuse reason with blasphemy?

Edited by Global Views 360 team